This post was going to be an email. In a research network that I participate in, it was suggested that the Distributed AI Research Institute’s (DAIR) statement on Palestine should be endorsed by our network. Some people didn’t like the statement, thinking that it was one-sided and inefficient, among other things. I liked the statement and said that it would be good to endorse it, as many others did. A member that didn’t like the statement accused us of being part of a propaganda machine while some others raised their concerns about DAIR not criticizing Hamas in its statement. The member who accused us of Hamas propaganda kept writing, so I was going to respond in order to clarify my position. In the end, the text became something different. So, I’m using it as an excuse to take up blogging again (I’ll probably move to some other platform though).

Most of my work is on state-sponsored violence in the contexts of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict and the Colombian conflict. Working on state violence doesn’t make you a very popular person. You receive a lot of insults and get used to being accused of a variety of things, among which the most common is terrorist propaganda. While most people reproducing them are probably not aware of it, these accusations are usually circulated in order to attribute lack of authenticity, agency, morality, and rationality to critical intellectuals, in an attempt to discredit and delegitimize them. Many people normalize the nation-state’s point of view to the level that my interpretation of armed conflicts ceases to be understandable unless I have some link to one of the armed parties. I’m used to this and the only thing really bothers me when it happens is my inability to convince people to question their positions.

As most colleagues working on political violence have probably experienced, you frequently get criticized for being biased when you challenge a state’s official narrative. This happens whether you’re in Azerbaijan, Peru, or China. People think that you are biased, insincere, or subjective, and eventually someone dares to suggest that you’re piece of shit. It happens all the time.

Now, I re-read DAIR’s statement to see what the problem may be. The statement does two things. First, it criticizes the political order of the region, which resulted in an apartheid system where Gaza Strip became a huge open-air prison. Then, it criticizes tech companies for their collaboration with Israeli and US militaries. Now, I would like to focus on why this statement was considered problematic.

First, it was argued that this statement was doomed to be inefficient. The poster said that he didn’t understand what such a statement can achieve and how it could contribute to peacebuilding. He, as many others do when they talk about political violence, wrote with a level of confidence and certainty that would make lifelong students of political violence extremely envious. But I’ll dare to say that this statement, along with various similar statements, does offer a fundamental contribution. A successful peace process, any peace process, has the delegitimation of the previous sociopolitical order as a prerequisite. It’s impossible to implement nonviolent conflict resolution mechanisms before discursively delegitimizing the current order and its violent structures. These statements are an important step toward that objective. They delegitimize the status quo, which subsequently leads to the legitimation of proposals calling for a complete sociopolitical transformation. The delegitimized sociopolitical order isn’t limited to Israel and Palestine, but it also includes the whole West Asia where a colonialist order was imposed starting from early 19th century, officially implemented following the WWI, and consolidated after the WWII. I’m currently writing about the historical part of the issue for an academic project, so I won’t go into details. What I want to say is that it’s acceptable that this part of the statement doesn’t mention Hamas because they aren’t the ones who have imposed this order, nor are they reproducing it. Hamas is a product of the current sociopolitical order, but it’s not one of the actors that are responsible for its implementation. By delegitimizing this order, it becomes more likely that future projects for a radical transformation are to be endorsed by transnational actors.

Now, obviously there are no tech companies collaborating with Hamas. So, it’s also understandable that this second part of the statement doesn’t mention them. So, why is it so common to expect that Hamas is being condemned in a statement like this? Probably it’s because Hamas has done something unacceptable and massacred Israeli civilians. Then, if I don’t agree with Hamas, why am I against including them in such statements? This obviously leads to the resolution that I must be a Hamas propagandist. Just like when I was an ELN or a PKK propagandist. I guess there can be no other explanations.

I would like to invite you to think that maybe there’s an alternative explanation. You can be reproducing and re-legitimizing the state’s perspective by mentioning both sides even when you’re criticizing the state’s human rights violations too. Why is that? That’s because you aren’t questioning the current sociopolitical order. You’re accepting it as a given and only questioning certain actions of the involved actors. This plays into the state’s hands even though it may be less desirable compared to declarations of unquestioning support. Now, the poster said that he also wants peace. Everyone wants peace. Anti-peace political actors are almost nonexistent at the discursive level. Everyone wants peace, but not this peace. They want another peace, which paradoxically requires more war. Students of political violence know that the overwhelmingly frequent way of legitimizing political violence is arguing that it prevents greater violence. We have to be violent now so that there’ll be less violence in the future. This is the most common argument. When you condemn both sides, you strengthen this argument. If both sides are equally of fault, maybe the stronger one can eradicate the weaker one so that there’s no violence in the future. This is a very popular solution to all ongoing armed conflicts and you hear it all the time whether in Turkey or in Colombia.

Now, what else is problematic about making a statement where you condemn both sides? This makes you reproduce one of the most common discursive strategies used to legitimize state violence. That’s blaming the victim, trajectio in alium if you prefer your terms in Latin. It’s a pretty old strategy, and it still works like a charm. By condemning Hamas in a statement about the military attacks targeting civilians in Gaza Strip, you imply that the attack is a result of the prior attack of Hamas. This is the legitimation given by the Israeli state. So, maybe they shouldn’t bomb Gaza, but also Hamas shouldn’t have attacked them in the first place. This opens a path to justification. You are now asking: Why did you attack and kill civilians? Since thousands of murdered Palestinian civilians cannot talk any more, I’ll respond instead of them. They didn’t. They had not killed anyone. Now, if an organization makes an immediate statement after the Hamas’ attack, I would agree with that. However, mentioning it in a statement regarding Israeli attacks means that you are putting the population of Gaza as a warring side. This is the pro-violence narrative even though it may not want to accept it. This happens all the time. You read a note about Turkish bombings in Rojava on international media, and most of them mention PKK and how it’s considered a terrorist organization. What does this mean? It means that Turkey is fighting against terror. Now, they do some morally and legally illegitimate things, but it looks like we can justify what they’re doing. They fight against the terror after all. Just like Israel, just like the US, just like most states. The terrorism argument has nothing to do with massacring civilian populations. Mentioning it in the same statement unavoidably associates the targeted civilians with the armed group.

Now, why am I writing this? Was it not sufficient to face problems and receive insults by people involved in the Turkish-Kurdish conflict and Latin American left-wing insurgencies? Do I need additional hatred and insults from pro-Israeli individuals and groups? My answer to this is somewhat personal. I’ve been very disappointed in contemporary academia for some time now. Every week I question my decision to stay within academia. I had always questioned the university as an institution and its role in reproducing the status quo, but I still respected it in some ways. I lost a considerable part of that respect in the last year or two. Bearing all my disappointment, worries, and anger, I think I usually forget why I’m doing what I’m doing.

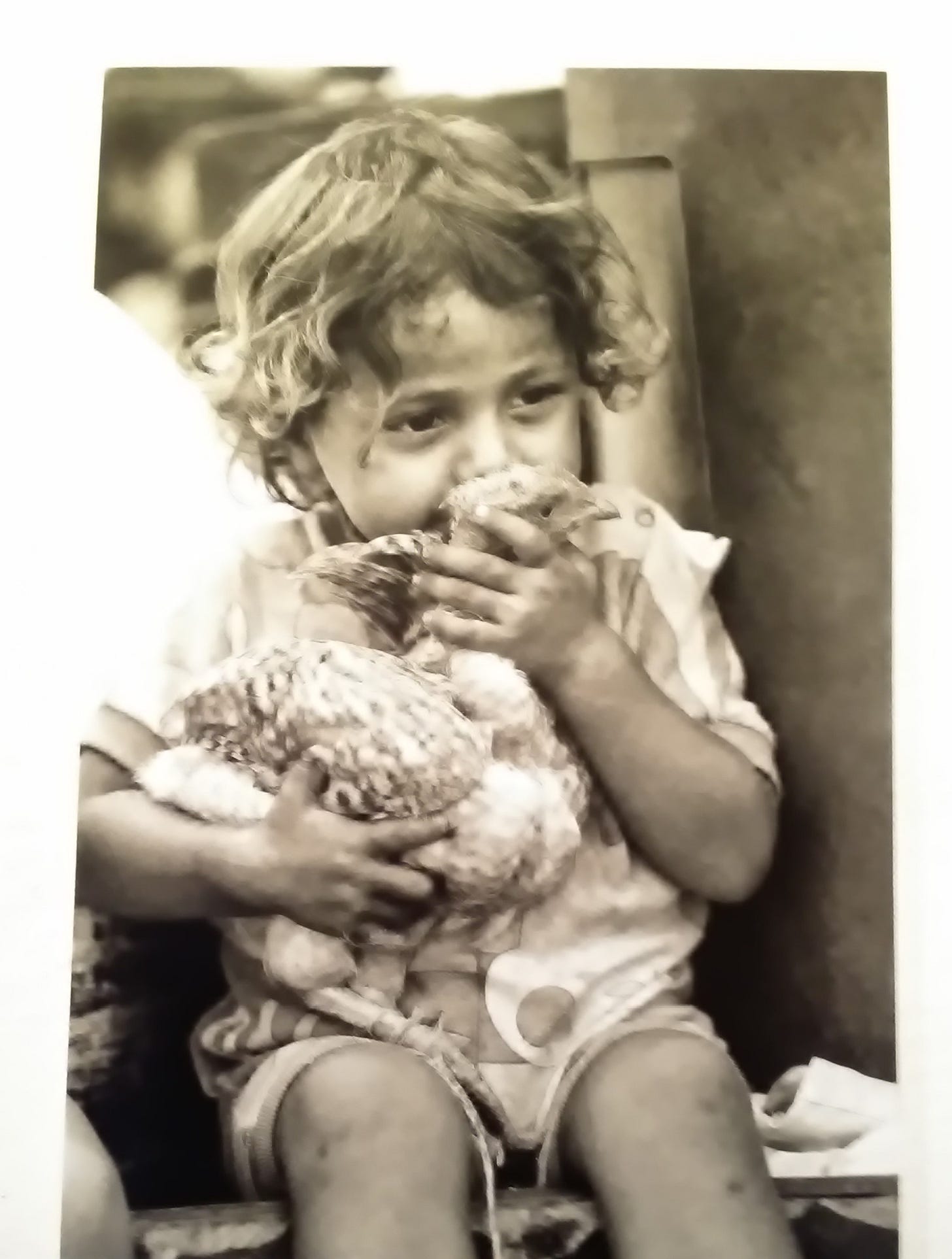

I didn’t want to study violence when I started my Master’s degree. I had enough violence in my life; I didn’t want more of it. I wanted to ignore the violence. I tried it for a while. It didn’t really work. I kept remembering that kid at his grandfather’s house who hated the curfews, and hated the helicopters, and hated the blackouts, and hated that he had to stay away from the windows. But what he hated most was that noise. All that noise. That noise didn’t let him read. It didn’t let him imagine that he was in a distant land, in a distant time, far away. It went on and on. He would love to shut that noise but he couldn’t. He had to listen.

That kid is gone now. I barely remember him. It has been a very long time after all. I inherited his love for mountains and his love for reading. And I still remember that he hated that noise. And when I forget how angry and how disappointed I am for the things that happened lately, I remember that I wanted to shut that noise. I know that kids in Gaza listen to that noise right now, the ones that are lucky enough to be alive. I guess they also hate that noise.

I know that it’s difficult to talk about the underlying problems of mass violence when it occurs. It’s not a time for calm debates. People lose loved ones, their lives are destroyed. It’s especially difficult when you say things that go against everything they’ve been taught since they were little kids. It’s not a convenient thing to do. But I didn’t start working on political violence to be popular. I do it to shut that noise. I plan to do whatever I think can help achieve that in the long-term.

The last time I was in Bogotá, we met with a friend who has lived in Kurdistan for many years. We met in a place now called the ‘House of Peace’. I told him it would be nice to sit in a place like that in Kurdistan one day. It would be nice in Gaza too. Colombia has many problems of violence and they’ll continue, at least in the short-term. But things look a lot better compared to when I used to live there. I remember sitting at a table in the ‘House of Peace’ and thinking how things changed had given me some hope. Things can change for the better after all, albeit a lot slower than we would have preferred. I think intellectual work can help things to change. I hope mine does one day. That’s why I’ve written this post.

I end this post saying that I’m very sorry if violence has made its mark on your life.

This is a wonderfully written note. I came here from the Labor Tech email thread and it helped me comprehend the discussion so much better. Timing matters so much, knowledge in time makes all the difference in the world. It's easy to forget that while trying to make a career in academia. And academia disappoints in so many ways. Here in my corner of the world, students who dare to speak out against state sponsored violence are put behind bars everyday by their own universities. But still it's always nice to stumble across folks who make it easier to understand something complicated. That's what convinces me to stay, despite everything. I'm grateful for your labor and effort to document and explain something as personal and perhaps painful as this. Aside from the obvious horridness around this particular conflict (and the stark parallels with experiences of living under authoritarian regimes elsewhere in the world), reading your note was a much needed reminder for me to continue to think about things critically. Thank you so much for writing this.